A talk given by Lord Chartres, the Dean of Her Majesty’s Chapels Royal, at the Residency of the British Ambassador in Moscow, 30 November 2018

First I want to express my own dismay and revulsion at what happened over the weekend in the shooting at the synagogue in the US. I imagine that we are all united in offering our condolences to our Jewish friends here and fortified in our determination to work together for a world in which such crimes have finally been relegated to history.

The city of Perge on the Aegean coast of Turkey is a ruin now but once it was a flourishing sea port in Hellenistic times which reached its height of prosperity in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century AD. The towers guarding the main gate survive and St Paul would have seen them when he visited the city with Barnabas at the end of the 40’s AD.

He would have seen a bustling city whose great days were still ahead with the construction of a great stadium and theatre. To the casual observer it must have been obvious that the future lay with the Emperor and the Roman Empire.

Augustus had rescued the Roman world from civil war and re-invigorated the ancient pagan cults. Temples to the Imperial Genius were being built over the Roman world. There is an inscription from the city of Priene [also on the Aegean coast of Turkey] which has come to rest in the Bible Museum in Frankfurt. It reads “the birthday of the god has brought glad tidings to the world”. The god in question was the Emperor Augustus and St Luke recycles this piece of imperial propaganda and incorporates it in the message of the angels to the shepherds announcing the birth of Jesus Christ.

St Paul arrived in Perge less than 20 years after the crucifixion and despite all the evidence of the Roman achievement, the apostle proclaimed that the future belonged not to the Emperor but to the followers of a crucified Jew in whom the promise that God made to Abraham that through him all the nations of the world would be blessed, had been fulfilled.

Roman religion had no such expectation. It seems to have been a culture not unlike our own. Edward Gibbon the author of the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” described it thus:-

The people believed that all religions were equally true.

The philosophers believed that all religions were equally false

The magistrates believed that all religions were equally useful

It was a time of great and understandable secular confidence.

This was very much the atmosphere when I was consecrated a bishop in 1992. This was the year of the publication of the book “The End of History” by Francis Fukuyama. The thesis was that with the advent of liberal democracy and market economics the human project had reached its consummation. Fukuyama is justly irritated by the suggestion that he had proclaimed the actual end of history. He insists that he was asserting that Liberal Democracy and Market Economics, the culture of Consumer Unbeliever International [Gellner] was the end- point to which history was tending. Areas of the world still lay in darkness but the consummation of the human project was already clear.

Religion might linger as a hobby for people with a taste for it but as a lifestyle choice no more significant than vegetarianism.

The Economist published an obituary of God in its Christmas issue in the year 2000 but only a few years later the editor of the Economist co-authored a book entitled “God is Back”. Certainly in the 21st century religious perspectives and institutions have a fresh salience for good and ill which they did not have in the 20th century.

The alarm generated among the Anglo-American elite by this sudden change is evident in a recent interview with the distinguished US scientist E.O.Wilson – “for the sake of human progress the best thing we could possibly do would be to diminish to the point of eliminating religious faith.”

The secular trend continues in NW Europe for reasons which should ensure that people of faith observe a proper humility when discussing questions of peace and human well-being. It was the hugely destructive religious civil wars of the 15th and 16th centuries which convinced many Europeans notably in France that some less subjective way of arriving at public truth must be found. Warring Christian absolutisms gave rise to an Enlightenment in France that was anti-clerical and even anti-spiritual.

The Enlightenment in England was different and Isaac Newton wrote more about the Book of Daniel that he did about Mathematics and until recently there were some places which seemed to defy the secular trend. Ireland for example was a very Catholic culture when I was growing up but in recent years child abuse claims and memories of the arrogance of the Church in its days of power have led to a cultural revolution.

Elsewhere however the picture looks very different. London is possibly the world’s most diverse city. The London School of Economics where I was recently giving a lecture on the “Faith and Leadership” course has students from more than 150 countries. In consequence the LSE is especially open to perspectives from other parts of the globe at a time when unchallengeable Western hegemony is fading and a new multi-polar world is coming into being in which the countries of the East will once more assume the significance that they have enjoyed for most of human history. There is considerable competition to enrol on the Faith and Leadership course which has speakers and students from all the major world faiths.

The significance of this development has persuaded the school to invest considerable resources into a new Interfaith Centre whose director is our Chaplain to the University.

At the same time stimulated by the international perspective I founded a new college named after my predecessor St Mellitus to train priests for this new world. This year nationwide in England more young people have entered training for the priesthood in the Church of England than in any year since 1963.

Part of the inspiration for this development comes from the charismatic movement which is the English face of a world-wide expansion of Pentecostalism. The religious sociology of South America has already been transformed to a point where even the leading candidate for the Presidency of Brazil, Mr Bolsonaro is an Evangelical Christian.

There are similar movements especially in Asia and Africa.

I am well aware however that the reason for E.O.Wilson’s outburst is fear that the resurgence of faiths world-wide could fuel destructive conflict.

The trouble is that mere appeals to ethical fraternity and abstract universal principles do not evoke in human beings one iota of the energy needed to transform lives or make peace across the divides of race and ideology.

An additional problem is that human beings always refer themselves to something or someone desirable or fearsome beyond themselves. In this sense everyone worships and ascribes worth to something beyond themselves. In the absence of a worthy object of worship the vacuum is filled with dangerous alternatives, the ersatz liturgies of political ideologies which are really spilt religions.

The major killers in the 20th century were secular messianic states like Nazi Germany which sought to build a pseudo-scieitistic heaven on earth and created instead a vast graveyard.

All people of faith have a responsibility to mine their own traditions for resources which promote reconciliation. One of the ancient churches in London fell victim to a terrorist bomb in 1993 and with the help of friends from many faiths, especially Cardinal Hume, the Chief Rabbi and a Muslim benefactor we rebuilt the church as a Centre for Reconciliation and Peace with the aim of preventing and transforming those conflicts which have a religious dimension.

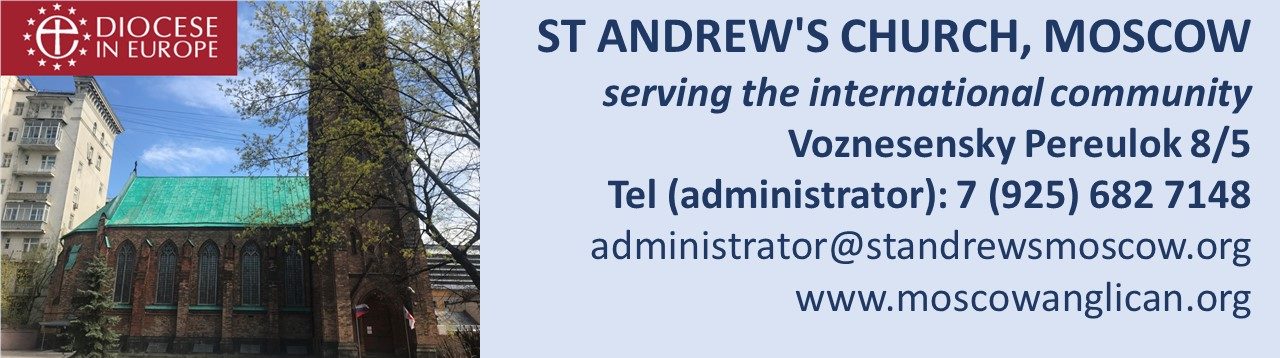

My Muslim friend financed a tent of meeting made of goats’ hair and Gortex which gives off a wonderful fragrance when it rains. It is the first Bedouin tent in the City of London although it uniquely has stained glass windows with the symbols for peace taken from every conceivable wisdom tradition. The church belongs to an international fellowship of centres of reconciliation called The Cross of Nails. St Andrew’s here is also affiliated. We are not an academic centre but have developed a number of practical resources for the work of reconciliation and we have been very busy since opening ten years ago.

One place of great importance for the future of the human future on this globe is of course China. There are proper anxieties about the freedom of religion there and especially among the Uighurs, the resources for surveillance possessed by the modern state are being used to the full. At the same time there are large religious communities undergoing revival, Taoist, Buddhist, Muslim and Christian.

Western missionaries were expelled in 1949 and a genuinely indigenous Chinese Church was left to face the test of the Cultural Revolution. When I made my first visit just after the Cultural Revolution there were perhaps only 400,000 Christians. Subsequently I have paid other visits as President of the Bible Society. We print most of our foreign language bibles in China – 20 million last year – and official figures suggest that there at least 60 million Christians both Protestants and Catholics and this is probably an underestimate. Most recently there seems to have been an encouraging improvement in relations between the State and the Vatican.

I ask Chinese friends why they have become Christians. They give three answers.

The Cultural Revolution was very destructive and there was a cultural vacuum. Then they associate Christianity with modernity and lastly the Church is very good for business because the usual zone of trust hardly extends beyond the family and the Church constitutes a much wider zone of trust which is conducive to good co-operation and business. The Chinese are very pragmatic

This is a time of promise and peril. Humanity is challenged by climate change, the existence of lethal weapons of mass destruction, and the potential of genetic engineering to entrench inequality between genetically enhanced humans and the rest of us, the naturals. As the tectonic plates of global power shift we need to be alert to the possibility of the Thucydides trap where a rising power challenges the incumbent hegemon and the result recalls 1914.

We all need to be allies at such a time to work for the promise of our century, a promise of unparalleled prosperity and freedom from disease and poverty for all peoples. Every one of the great wisdom traditions of the world has a vision of authentic human flourishing. We ought to be very humble in the face of our failure to date to build adequate alliances and do all that we can to promote a common agenda for human flourishing but the call to do better is urgent.